08.09.2021

Home / News / Creative Health /

“I think it’s helped me deal with lockdown. It’s helped me sound out what I’m thinking. I’ve been chasing a little flicker of understanding. Trying to think and digest and let it filter in. Or else you drown in your own thoughts, don’t you? If you’re left alone with them too long.” – M, participant quote.

Necklace of Stars was a project designed to reach out to isolated older people in Derbyshire, with home visits to make poems and art. But when the pandemic started at the same time the project launched, the whole thing was at risk of being cancelled. It took a few deep gulps to move the project from face-to-face workshops to working over the phones. Now the home visits wouldn’t occur — but would phone workshops be anything like a substitute, for participants and for me?

For the last 20 years I’ve been making poems with groups of people — often working in tandem with artist Lois Blackburn — often using experimental approaches. The idea of an experimental mindset is that nothing’s fixed, any/everything can become part of the work. Even if the work fails in some senses, it isn’t written off, it can be observed and learnt from.

As it happens, making poems by phone hit me with the force of a revelation. The depth of the encounters, emotional and artistic, was remarkable. It became clear that solo poem workshops were not only possible, but could blossom in these new, fearful circumstances. What follows is a short account of making poems over the phone, from May 2020-March 2021. Interspersed with my narrative are quotes from participants and extracts from my project diary.

“I was feeling fragmented, fragile. I was working through that and trying to find strength and determination. So I grabbed onto the writing. I wasn’t aware of it at first, just playing with words and rhymes. And then it became clear to me, I’m speaking to myself and for myself…” – L, participant quote.

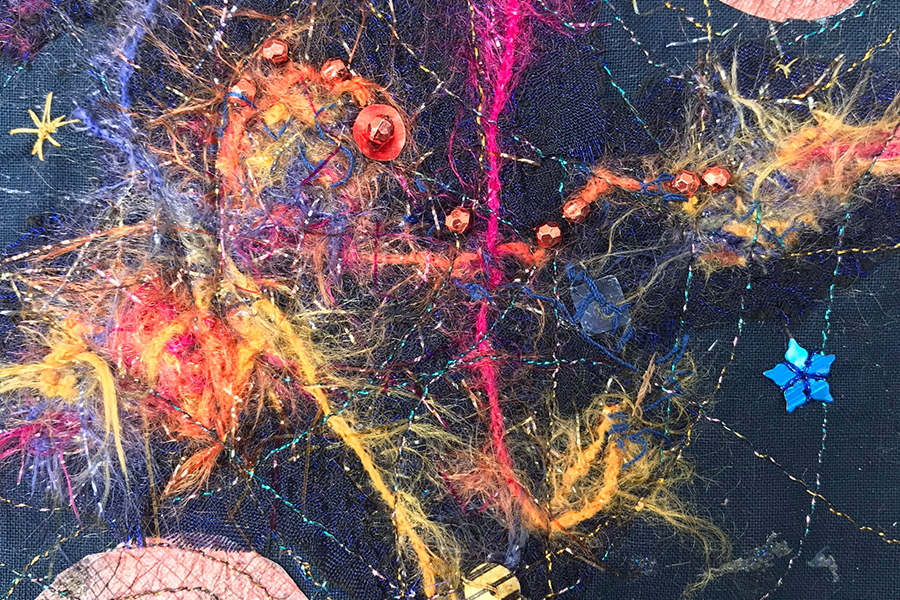

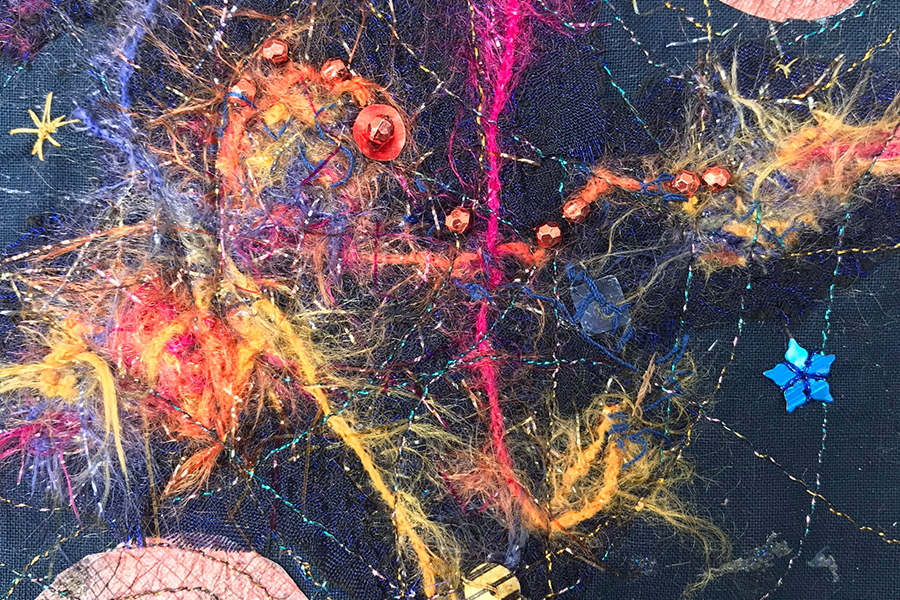

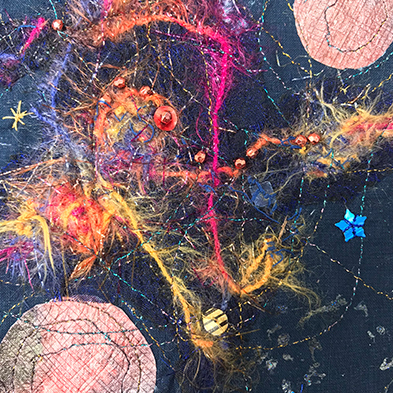

Left: Beaded Star, Margaret Giller, June 2020

With poems, we question, reflect and reconstruct ourselves. They’re an internal communication, with the self. They are also a messenger sent out to the world to say “I am here”. They tell stories, histories, fantasies, truths and lies; poems can strip away illusions, or pile up mysteries— sometimes all in the same verse. Poems have been around a long time, for good reason, however they’re usually considered to be a luxury. In lockdown, poems became part of the rescue package.

A tumble of ideas and contradictions is exactly what many people wrestled with during the pandemic, as they experienced something close to solitary confinement. Especially older people, shut away with just their own thoughts and a radio or TV. “Doing time” like this can be torture — and of course solitary confinement is used as a form of punishment. It was important that we not only used our project for creative distraction, but that we spoke to the incessant worries in people’s heads.

“Y was very nervy today. I could almost see her quivering physically, as I listened to her shaking voice. But talking seems to bring some calm, the companionship of another person is steadying when she’s lost her anchor to the world. I have encouraged her to talk about and write about some of these fears, as well as enjoying the distraction of writing about childhood adventures. It can help to write about the worries, put them down on paper and they sometimes don’t swim about in your head so frantically. A long time talking, calm slowly descending.” – PD project diary.

Being alone is not a bad thing per se — it’s only by spending periods diving into your internal world that you’ll find space to hear yourself and find time for that voice, once formed, to be articulated. Spare time was forced on us in 2020, so this was a great opportunity to write. Learning to write is partly about learning the art of solitude. To make things that require time and repay it with depth and resonance. In this way, perhaps the pandemic could be turned to advantage?

The Necklace of Stars theme of childhood lullabies, stories and the night sky was a great stimulus for some of the writers:

“There is an aura off the starlight, it’s very powerful. It draws us to it, gives us peace and makes us feel our place. Now I’ve got the time I’m coming back to those questions. Instead of taking life for granted, I’m exploring it. Opening my eyes to the starlight. If you can’t see it, you can’t write a poem about it.” – N, participant quote.

But other people wanted a different kind of space. They needed to address what was going on in the world immediately around them and in their own heads: “Stories come into my head. All the different ways people have reacted to this time of isolation and shielding. Each of us has a different idea of how we can react to now and how we can rebel. I’m trying to write about how this situation affects each and every one of us. This project is about the stars leading us out of despair. Demonstrate or rebel, and then everyone knows you still exist.” – J, participant quote.

J had been shut away in her house since November 2019, first with illness, then with lockdown. She felt neglected and overlooked. (“I think I’ve been forgotten.”) She wanted to express her anger at the chaos and the political opportunism she saw on TV. However, she had some problems recalling the details of a conversation and in holding ideas in her memory, so I jotted notes during our conversations, which I’d email and she’d later work up into stories.

“We have come up with a bespoke way of working around her problems and making sure that her writing deals with issues she feels important. We have invented some writing exercises for her. She has drawn up a list of imaginary rebellions that she can write, and share via the blog, as opposed to carrying them out in real life. People who read them on the blog can emulate them if they want. So far, the rebellions are to sit down in Tesco’s and scream, to chain yourself to a tree on the HS2 route…” – PD project diary

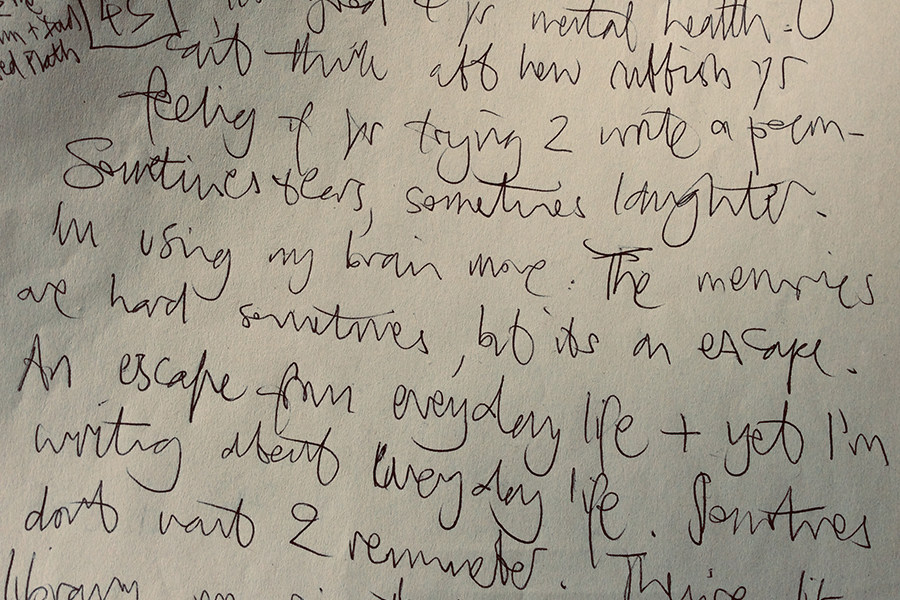

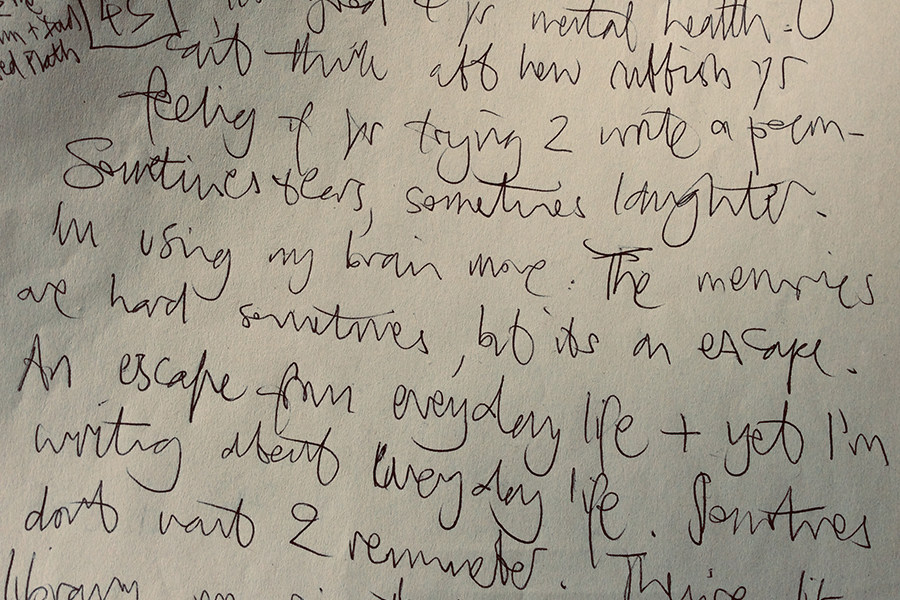

Snapshot of Phil Davenport’s diary

The workshops were often customised to people’s individual needs and if possible I tried to build in progression and a sense of challenge. For some people talking and writing became a way to unburden, and a way to make sense of Covid. But the deal was struck that some of the work had to be frivolous and jokes were a necessity.

The calls generally lasted anything between 15 minutes to an hour. Very occasionally, if I felt the need was really there, a call would stretch to 90 minutes. Over the course of the day I would make around six calls, sometimes eight or nine. By the end of some days, my head was spinning and my lungs felt as if they were running out of oxygen. I talked myself out. In the evenings I’d go for a walk along our local river in Manchester, dodging the runners and the groups of young drinkers, trying to find peace and a space to relax. These calls were different to my usual workshops, not just because they were delivered over the phone, but because I was also inside the same problem as the “participants”; we were all living the pandemic together.

We talked about the lockdown, people spoke frequently of long tedious days followed by nights of bad sleep. They admitted fearing the disease and what this fear did to them. I listened, knowing that I was in the same predicament.

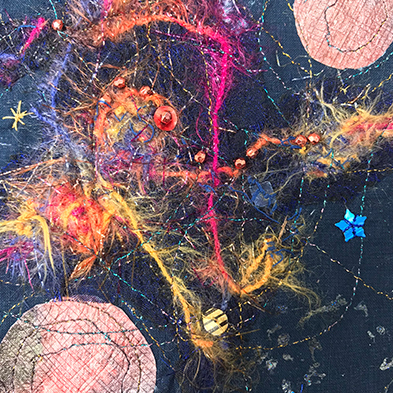

Left to Right: Star Embroidery, Joan, May 2020 & Metallic Thread Beadwork, Jean Wells, February 2021

Being solitary meant that some aspects of life were magnified. Older people often carry grief, for lost partners and friends, and part of travelling into memory meant encountering these presences. But in the case of T as with several others, we then moved onto the memories of childhood for a minute exploration of that part of life. Childhood forms us and the memories are among the most potent that we carry. Here is a series of thoughts from T:

“Look across from my doze in the chair. Look across and you think they’re still there, the one you have lost. There isn’t a word in English for this grief, I call it “endurement”. Leaving the hospital as she was dying, I saw shadows on the wall. My shadow bifurcated into two and then it became one shadow again. It was like a prediction of what was to come.”

“The virus makes you go into memory because the future is so uncertain. I plunge into memory and yet it’s distorted. The memories are juggled, they recede, distant things seem like yesterday. A wonderful, happy day with my wife before she died. A day at the beach, seems so close and yet it’s a decade gone. I used to write for her and she used to write for me. So, to put poems on this blog is luxury. To write for someone else again…This has got me going back. There is a danger of becoming reclusive, but what we doing here is both useful and fun.”

“Writing takes a big chunk of my day, it’s very important to me just now. What am I writing? I’m living in the past, not the recent past which is full of grief for me, but the past of childhood. I’ve stepped beyond the grief and gone right back to something that’s relatively harmless. And going back to these memories helps me to know myself, I see aspects of the child that are in me today.” – T, participant quote.

In the middle of lockdown, a certain kind of freedom was found. Face-to-face workshops are very affected by group dynamics and intimacy for individuals is at times stymied by the wider group. There are many kinds of power politics in such groups. Working one-to-one over the phones can allow intimacy to occur more easily. If you can’t see the listener’s face, it frees you from thinking about their judgements. It also stops people performing for the group, moving to a more truthful encounter with themselves:

15 mins – “X was very jolly, as ever, yet underneath the jolliness is a deep concern. She is writing better poems, not being so chatty, opening up the areas that she’s really interested in. As with the jolly persona, the poems are now putting aside their masks and being true. X’s clearly enjoying playing about with the words, having fun, but there’s a realisation that she can tie this to a deeper purpose, if she wishes. I emphasised that there’s always a choice — how deep we go is a matter of how adventurous we’re feeling at any given time and that we always need a reserve of extra energy to come back with.” – PD project diary.

Left: Embroidered Stars, Joan Beadsmore, June 2020

Out of these encounters came a wealth of deeply-felt writing. If you go to the arthur+martha blog you’ll find poems and testimonies there; a mirror of the moment. The emotional intensity of the work was part of the intensity of this time and it made the writing shine. It was wonderfully uplifting to witness people alchemising something bright out of this dark moment. Some poems were modest little meditations on the garden, the neighbourhood, yet they were a big refuge. Here, seen on a local river:

Such a little duck,

holding her own in that strong current,

such determination to rid herself

of whatever was troubling her –

mud, weed, algae, parasites

Minutes went by – then suddenly she stopped,

stood upright, shook off the last drops

from her feathers in a shower of light…

leaving a clearer space in my mind and eyes.

– From On a Day of Sorrow, Lorna Dexter

Phone calls and poems are made of the same stuff — words. But body language is cut out of phone calls and all that’s left to gauge the engagement of the other person is their tone of voice and the pauses between. On a few occasions the pause was a big hint to end the call.

Which takes me to the disadvantages of working over the phone like this. Most brutally, it kept people who were isolated in their bubble. The craving for human contact, for touch, for all the little incidents that come from being in the same room with someone, those precious things were absent. For some people a phone call was a bit too unrelenting, they wanted to be able to take a break and listen to someone else. The absence of the wider group also meant that the writers felt alone in their writing. Although most of them had their work shared on a blog, that wasn’t really enough. What they needed was a group to respond, to act them on and to offer ideas and criticism. They wanted to be part of a bigger conversation, in the human swim, but human connection is the big gap that can’t be bridged in a pandemic.

And the situation hung over me me too. Human connection is the big gap that can’t be bridged in these circumstances. And this applied to me too. In such a moment you can become a very important person in the participants’ circle of emotional support and that brings responsibility and with it pressure. My remit was clearly a creative maker, but I felt very strongly — almost felt beholden — to give people the phone time they craved. The project wasn’t only about creative making, it was clearly impacting well-being. And the encounters weren’t always happy ones. Several people were in depression, fear, desperate loneliness, grief — and one was dying. It was difficult to see the fading of this older woman over a period of weeks. And yet this experience was part of the fabric of the time. Death was in the news, was all around us. It was strangely unsurprising to meet it at last, via a phone call:

“Z says she’s feeling very rough and the antibiotics are causing sickness for her. However we worked on a poem fragment in which she recalled her husband to be and her as the younger selves, looking up into the night sky and identifying the stars. A lovely little memory, which I jot it down for her poem about the night sky.”

Z – Brief talk, cut off by a call from her befriender. She can’t walk unaided, sounds sad.

Z – Z died a few days ago. I spoke to her daughter, who was shaken but wanted to talk. I’ve promised that I will send some of Z’s poems. She wants to read them at the funeral, as a way of hearing her mum’s voice once again. A sad little conversation, but not a surprise. Z was sounding tired and fragile; with each call she seemed to diminish a little bit, become a little bit mistier. – PD project diary.

Left to Right: Shooting Stars, Marylyn MacLennan June 2020 & Psalm33:6 Inspired Embroidery, Pamela Walker, June 2020

I’ve been running workshops a long time — in hospitals and homeless centres in particular — and things can go seriously downhill for people in those situations. There have been many deaths, many breakdowns, many overdoses, great pain. To witness these things is sad but doesn’t necessarily cause damage to me, providing the boundaries of my role are clear and I feel that what I’m doing is helpful. Sometimes to simply be a distraction or light entertainment is a great help when life is difficult.

My role was clear: I made calls for one day a week only. I answered emails on that day and at the end of it I wrote a reflective blog piece, or posted participant quotes or poems. Then it ended until the next week. In other words, I could switch off, which is crucial for work like this.

It was also crucial that I was not alone. I had an excellent support worker (in Sally Roberts) who had worked with high-risk groups, was never phased, always willing to talk. Sally’s unflappable presence was the touchstone I needed. And her organisational support was peerless, which took away the managerial and logistics pressures that would’ve hung over my head in a self-directed project. If participants needed extra support, befrienders, helplines, calls to the doctor, Sally stepped in. When we spoke, her young daughter would sometimes chip into the conversation with non-sequiturs which ended our calls — occasionally very serious calls — with gales of welcome laughter.

When I finally stopped in Spring 2021, I felt like I’d run a marathon — exhausted but also with a sense of achievement.

If I can draw one conclusion from all this, it’s that poetry phone calls not only work as an antidote to isolation, but occasionally they’re preferable to group work face-to-face. In this new normal, maybe we can learn from the recent experience of restrictions? Phone poetry workshops could be a way to reach out to people more discreetly than via a group, and in a way that fits their needs. For example, phone poetry could work very effectively allied to social prescribing, giving an opportunity for both boundaries and intimacy. One-to-one workshops are usually expensive, but phone calls mean travel is irrelevant — the huge travel cost/time that the original Necklace of Stars project entailed was used as phone time instead, actually giving participants far greater contact time with the artist. Extend this and the calls could reach out nationally, or even internationally, allowing people to cross boundaries and borders without travelling.

In a grim year of lockdowns, fear and loneliness, this small glimmer showed itself. There’s a detailed evaluation of Necklace of Stars by researchers from Nottingham University and this independent evaluation showed that people benefitted from the calls. So did I — in this time of the plague, I was able to be useful, by means of (of all things) poetry.

Written by Phil Davenport

A Necklace of Stars is an Arts Derbyshire Project supported and funded by Arts Council England and Derbyshire County Council Public Health

Submit your news items to editor@artsderbyshire.org.uk or fill out this news submission form.

You can also register as a member to list your arts business and events in our directory.

Find out what’s on with the Arts Derbyshire newsletter.

Artists, creatives, cultural providers, arts and health specialists – Sign up for one of our professional mailing lists.